To make a weather forecast and simulate future climate scenarios, scientists use numerical models that carve up Earth’ surface into a large number of grid cells, vertically and horizontally, constituting very small zones.

The size of these cells is what is generally called the resolution of the model.

The higher the resolution, the more cells there are.

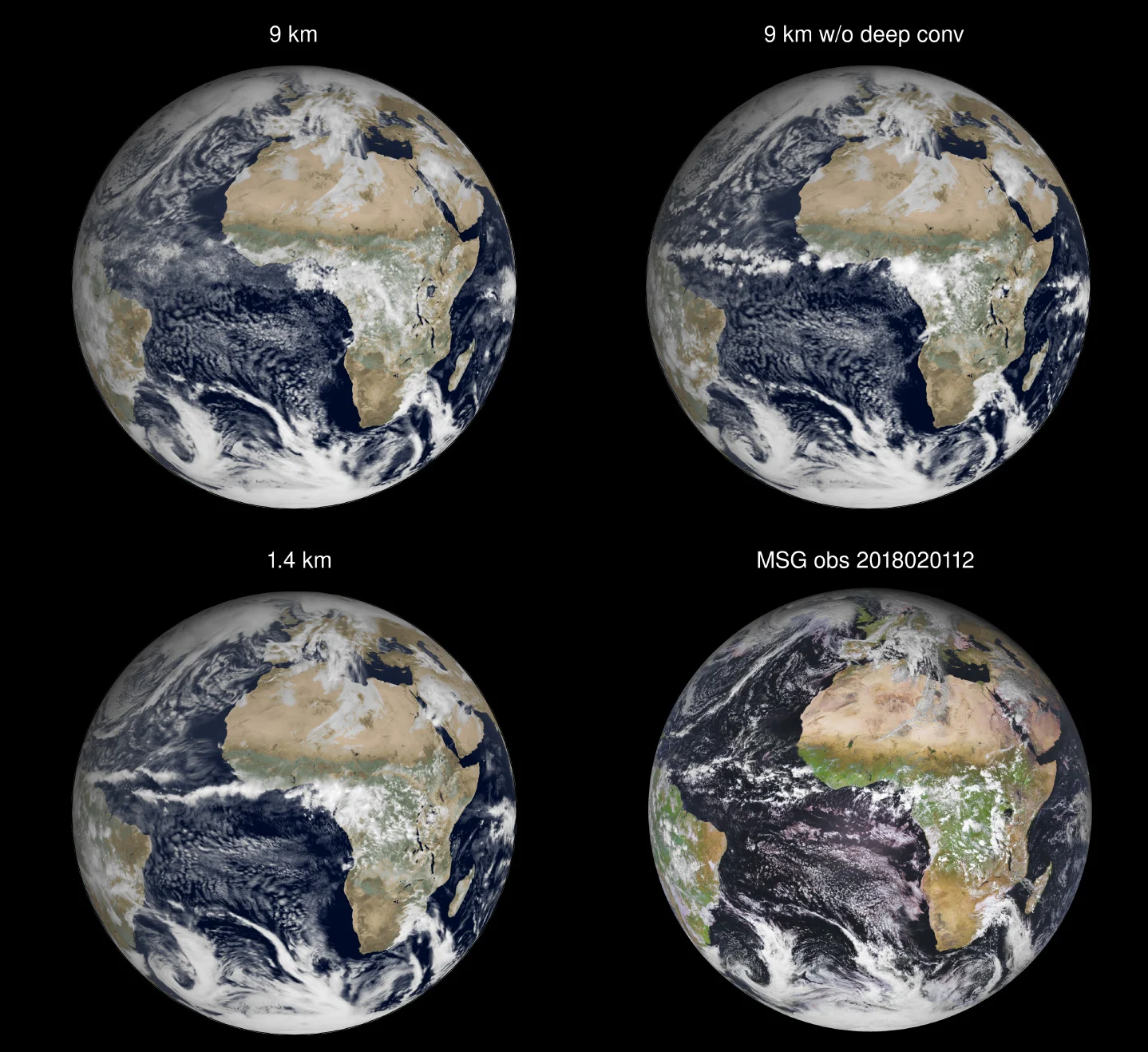

The models for global weather forecasts running at operational centers use a resolution of 9 km at best for the atmosphere and land surface, while global climate models generally use a resolution of about 100 km, and occasionally a resolution of at best 25 km.

The highest resolution used for the ocean and sea-ice for both weather and climate simulations is of 25 km.

Weather forecasts have a time horizon of about 15 days while climate models are used for projections of Earth’s climate evolution decades to centuries ahead.

At the resolutions used today for global weather and climate predictions, a number of important small-scale processes which are important for both extreme events, and the evolution of the climate system, are not directly represented by solving the equations of the atmospheric or oceanic flow.

Small-scale processes that are not explicitly simulated need to be therefore parameterised, meaning that their effects on the atmospheric or oceanic flow are accounted for through simplified assumptions.